Launch your professional website today here

The Noble Knight: Kamel El-Telmissany – A Forgotten Pioneer of Egyptian Surrealism and Revolutionary Cinema

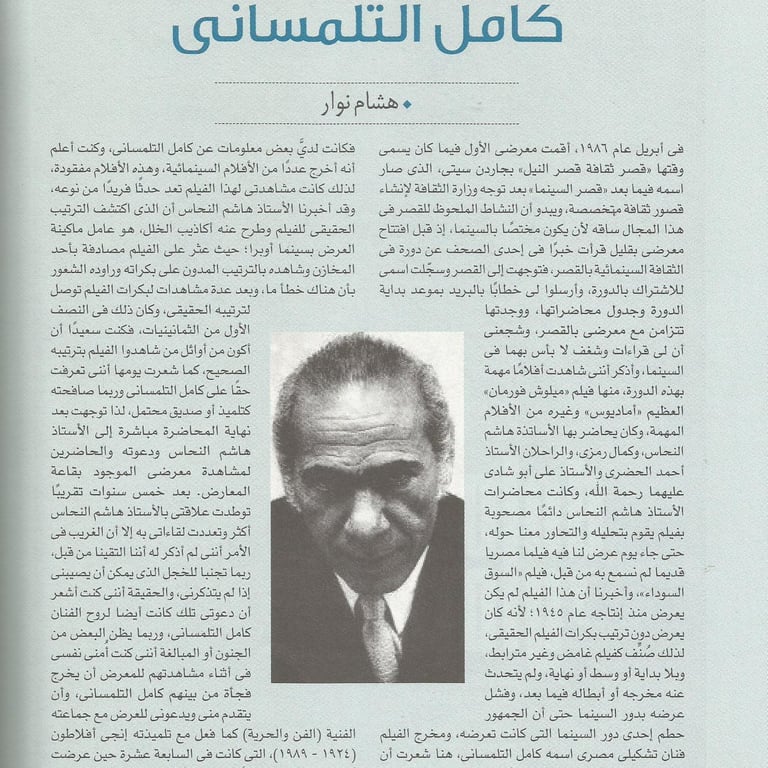

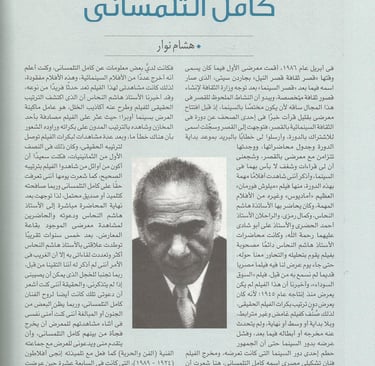

By a visual artist and witness to legacy – Originally published in Ebda'a magazine, October 2019 issue. In April 1986, I held my first art exhibition at what was then known as the Qasr El-Nil Culture Palace in Garden City—a venue later renamed “Cinema Palace” following the Ministry of Culture’s initiative to specialize certain cultural centers. The change made sense: the center had increasingly become associated with cinema. Just before my exhibition, I read in the newspaper about a film culture course being held there. Driven by my deep interest in cinema, I signed up. They sent me a schedule by post, and the timing of the course coincided with my own exhibition. I remember being especially excited by the selection of films, including the great Amadeus by Miloš Forman. The lectures were delivered by some of Egypt’s most respected film critics and scholars: Hashem El Nahas, Kamal Ramzi, and the late Ahmed El-Hadary and Ali Abu Shady. El Nahas’ sessions stood out in particular; they included both a film screening and an in-depth critical discussion. It was during one of these lectures that he showed us a forgotten Egyptian film we had never heard of before—“The Black Market” (1945). The film had been shelved since its release due to being screened with its reels arranged incorrectly. The result was a disjointed narrative with no beginning, middle, or end. Its reception was catastrophic—audiences rioted, and one cinema was even vandalized. The director, it turned out, was none other than Kamel El-Telmissany, a renowned Egyptian visual artist. That screening changed everything for me.

HESHAM NAWAR'S ARTICLES

Hesham Nawar, Visual artist & Art critic

10/19/20293 min read

"Black Market" movie poster, 1945.

Rediscovering a Lost Masterpiece

El Nahas explained that a projectionist at the Opera Cinema had accidentally discovered the film in storage and realized the reels were out of order. After carefully rewatching and reordering them, the true narrative of the film emerged. This took place in the early 1980s, and I had the rare privilege of being among the first to watch this film restored to its intended form.

After the screening, I invited El Nahas and the attendees to visit my exhibition, held in the same building. It was more than just an invitation—it felt like a silent homage to El-Telmissany himself. I imagined that the artist’s spirit might somehow emerge from the audience to greet me, perhaps even inviting me to join his Art and Liberty Group, much like he once did with his protégé, Inji Aflatoun, who exhibited with the group at the age of 17. I was 19 at the time.

Kamel El-Telmissany: Surrealist, Realist, or Revolutionary?

In January of that same year, the prominent art critic Samir Gharib released Surrealism in Egypt, a book that ignited a cultural firestorm by documenting Egypt’s unique surrealist movement. I had already known a little about El-Telmissany as both a filmmaker and visual artist, and his missing cinematic works only added to the mystique surrounding him.

Surprisingly, The Black Market wasn’t surrealist at all. Rather, it was deeply realist, punctuated by poignant songs and bold cinematography. Its lighting, camera angles, and expressive mise-en-scène intensified its emotional charge. While surrealists like Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí had famously infused cinema with dreamlike logic (Un Chien Andalou, 1929), El-Telmissany chose to ground his work in painful reality, addressing Egypt’s socio-economic injustices head-on.

Why didn’t he infuse his debut film with overt surrealism? Perhaps because El-Telmissany understood the limits of elite gallery audiences. Cinema, he believed, could bring art to the people—and he meant to reach the suffering classes, not merely entertain the bourgeoisie.

Beyond Surrealism: A Political and Artistic Awakening

El-Telmissany’s artistic beginnings were closely tied to Albert Cossery, the Egyptian-French writer who began as a poet. Together, they joined the Art and Liberty Group, co-founded by Georges Henein, whose 1940 manifesto was accompanied by a drawing from El-Telmissany. Yet despite his membership, I find no clear surrealist markers in El-Telmissany’s visual work.

Even within the group, some participants, like Mahmoud Saïd, weren’t surrealists either. Their focus was freedom, not strict stylistic alignment. This is evident in the group’s vehement anti-Nazi stance and their declaration "Long Live Degenerate Art!"—a direct counter to the Nazis' condemnation of modernist aesthetics.

El-Telmissany’s paintings are marked by thick, rough black lines and anatomically distorted forms—techniques that defied academic norms and aligned more with expressionism than surrealism. His use of vibrant, primitive colors and spiritual undertones recall the works of Georges Rouault and Max Beckmann, though his figures are more tender than anguished.

One recurring motif is the use of giant nails piercing human bodies, a possible allusion to crucifixion—but taken further, portraying mass suffering rather than singular sacrifice. These works evoke pain not as a tragic inevitability, but as a call to collective resistance.

The Cinema of the Oppressed

Kamel El-Telmissany did not merely document the suffering of the Egyptian people—he lived it. During WWII, the Egyptian economy was exploited by British forces, enriching a corrupt elite while the masses starved. The artist found himself creating works about the pain of the poor only to have them purchased by the privileged. Disillusioned, he turned to cinema as a more democratic and accessible medium.

His decision was both ideological and practical. He left the Art and Liberty Group at its peak and quit painting altogether. His emigration to Lebanon in 1961 was a final act of self-exile—his second migration, after moving from rural Qalyubia to Cairo, abandoning veterinary studies to become an artist, then filmmaker.

A Final Farewell

By the end of his life, El-Telmissany was working with the Rahbani Brothers and Fairuz in Beirut. On March 3, 1972, Fairuz received the news of his passing while on stage. She turned her back to the audience, tears flowing, as she sang with a trembling voice.

Though he passed away young, Kamel El-Telmissany left behind a legacy of radical compassion and artistic defiance. A true knight of Egyptian art, he never betrayed his principles nor compromised his vision.